Monte Carlo Simulation of Type 1 Superconductors

A summary of my experience with ISSYP

Try out this interactive simulation by lowering the temperature slowly:

If you want to know more, read the explanation below

Butterfly Effects

I was sitting in a high school classroom listening to a talk on modular arithmetic from a PhD student practicing their PhD dissertation. I was in 11th grade, and I was learning as much as I could about math and physics, in some feeble attempt to try and figure out what I was going to do with my life. At the end of the talk, the speaker asked the classroom of high school students if there were any questions. As the talk was somewhat short, I did not have any in-depth questions, nor did I expect many from the other students. To my surprise, the student sitting next to me started to ask in-depth questions. Intrigued, I struck up a conversation with him after the question session. He told me about a summer program called ISSYP (International summer school for young physicists) held at Perimeter Institute. He had attended this program the summer before, told me about some of the physics he had learned there, and encouraged me to apply. I though it was a marvelous idea, and then promptly forgot about it for 6 months. Later that year, I was trying to figure out what I would be doing that summer, and I remembered our conversation. I applied and a few months later was accepted.

Attending ISSYP

At the end of that school year, I flew out to waterloo to attend ISSYP at perimeter institute. When I got there, I met the most incredible group of people. Attending along with me were 20 young students selected from within Canada, and 20 were selected internationally. We quickly became acquainted and attended the program. The physics camp itself was fascinating, being a mixture of physics lectures, fun projects, and activities, key-note lectures from famous physicists such as Lee Smolin, Neil Turok, Art McDonald, and many more. During the camp, we toured SnoLab, a neutrino detection facility 2km under the earth, as well as the institute for quantum computing at IQC. This for me was one of many highlights of the trip. Near the end of the camp, we were paired up with an advisor and lead through a more in-depth study of a particular field of physics. The subjects varied, with numerous interesting fields of study such as cosmology, loop quantum gravity, solid-state physics, string theory, quantum cryptography, and general relativity among others. I was interested in solid-state physics, as this is the field of study which explains the inner working of superconductors.

Splitting into groups

I was paired up with Lauren Hayward Sierens, a researcher at perimeter institute. She is a researcher in solid state physics with a focus on superconductors, so myself and 5 other students learned from her over the course of a few days. During these sessions, she walked us through developing an algorithm and some code to simulate the quantum functionality of type 1 superconductors. The rest of the article is concerned with this. Below you will see a version of the superconductor, now implemented in JavaScript instead of python, and running on p5.js, a 2d rendering library that uses web canvas for performance.

Super Conductor Simulation

This is a visual representation of the quantum phase states of the cooper pair bonding present within a type I superconductor. This particular simulation uses the XY Monte Carlo random sampling method to get a running time that is reasonable on a modern pc. Running a perfect simulation of a type I superconductor without this statistical approximation would require the computing strength of a supercomputer. For this reason, the Monte Carlo random sampling algorithm is a very powerful tool as it allows semi-accurate approximations that can help develop an intuition for what is occurring physically.

What is Super Conductivity?

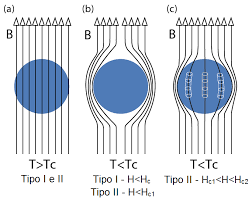

Superconductivity is a state that certain materials can take where they have zero electrical resistance. This has some weird side effects, the most prominent being that superconductors repel magnetic fields. These superconducting states are normally achieved at super low temperatures. The holy grail of superconductivity would be a room-temperature superconductor. This would have applications in almost all aspects of day to day life.

How are Super Conductors described?

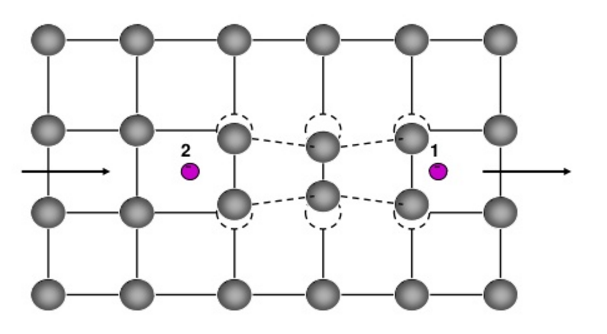

Type I superconductors are described using the BCS theory model, first proposed in 1957. It won the Nobel prize in physics in 1972. In BCS theory, the material is modeled as a lattice of positive ions with a sea of free electrons. As an electron moves through this lattice, it attracts the positive ions towards it. This region of higher positive charge can have a delayed attractive effect on another electron. Thus, these two electrons can have an indirect "attraction". This pairing is called a cooper pair; a quasi-particle. Because pairs are continually interchanged, the energy required to break anyone cooper pair is the energy required to break all of the pairs. Electrons on their own are fermions and obey the Pauli exclusion principle. As such, electrons cannot normally share quantum states. A cooper pair, on the other hand, is a boson and can form a bose-einstein condensate. This state of matter allows for the sharing of quantum states, and in this case, facilitates the co-existence of all of the cooper pairs in the lowest quantum energy state.

Type I and Type II Super Conductors

There are thirty pure metals which exhibit zero resistance under low temperatures. These are type I superconductors, and also the type that is being modeled by this simulation. These are modeled by BCS theory and are relatively well understood.

Type II superconductors are those which are made from alloys and cuprate like substances. They have the interesting property of flux pinning, where they pin the superconductor to its position in a magnetic field when in-between the first and second critical temperatures. BCS theory fails to accurately describe type II superconductors. There are no fully worked out explanations as to how these work.

The XY Model

This is a model commonly used to describe superconductivity and superfluidity. It considers how each relative energy state interacts with its four nearest neighbors. This is not a perfect representation but gives a good approximation.

A quick note on Statistical Mechanics

In superconductors, microscopic properties are used to infer and analyze important macroscopic behaviors. With the computational power available, it is impossible to know all information about all of the microscopic states. Statistical Mechanics uses probabilities and statistics to calculate the expected state of the system on a macroscopic level. This means that there are some inaccuracies and "guesswork" involved with this simulation.

Meissner Effect

The Meissner effect is an important property of superconductors. It occurs when the material is making a transition from its normal state of matter to a superconductive state. When this occurs, it locks the current magnetic field within the superconductor or repels it depending on if it is a type I or type II superconductor

Monte Carlo Random Sampling

The Monte Carlo random sampling method is a broad class of computational algorithms used in many areas such as condensed matter physics, statistical, analysis, finance, machine learning, and graphics. The core principle is that one can learn about a dynamic and complex system by simulating it with random sampling to obtain "average" numerical results. It uses principles of randomness to provide solutions to problems that are often deterministic in nature. This is useful for problems that have exponentially growing computational needs and time complexity.

PseudoCode

- Generate an N by M lattice with "rotors" with random phase angles indicating the relative quantum energy state of the Cooper-pairs.

- Specify the temperature of the "heat bath"/ canonical ensemble.

- choose a random lattice site and choose a random new possible phase for the rotor.

- Calculate the energy difference between this lattice and its 4 nearest neighbors using the XY model.

- if the change in energy from the new possible random phase is deltaE<=0, accept the move.

- If deltaE > 0, accept the change with a probability of e^(deltaE/(kBT)). This equation is dependent on the Boltzmann constant, temperature, and the change in energy.

- Repeat from step 3.